|

|

| Home › Articles › Here |

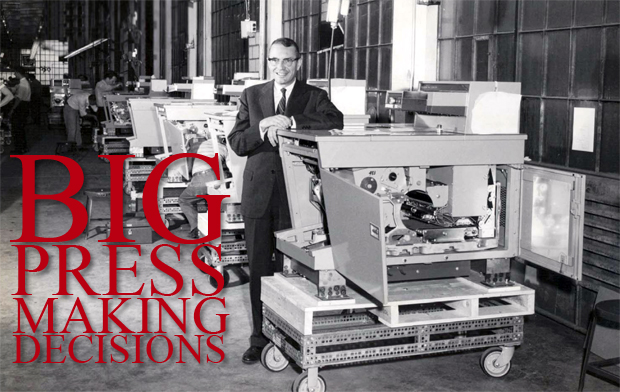

Joseph Wilson, Xerox CEO from 1946 to 1966, with the company’s first automated copier, Xerox 914, a key piece of printing machinery evolution. |

|

||||||||||||||

| By: Nick Howard | Date: June 2010 | Contact the Author |

|||||||||||||||

| “You’re wrong!” – Words I have heard

too many times over the past couple

of years when visiting a printing

company to evaluate a used press. This particularly

irritated owner then echoed what

so many others have such a hard time believing,

“There is no way my machine

could be worth such a low amount. I have

always been able to sell my equipment for

as much or more than I paid for it.” Believe me, I feel their pain, having spent the past 40 years of my career both as a re-seller of printing machinery, as well as a certified appraiser. I come face to face with executives seeking to understand what their assets are worth, but not always liking what they hear. I did not have the heart to tell this printer that if he wanted I could list his used press next to a Crosfield Magnascan and Miehle Horizontal. The printing industry is right now in the midst a watershed moment, which is most obviously being determined by the many new forms of on-screen communications and online media. It is quite clear that printing’s fear of the demographic shift in media consumption is now fully underway. The public consumption – demand – of graphic communications in terms of print versus on-screen was always going to be determined by age, not if but when younger generations so tightly wound with the World Wide Web took on the majority of purchasing power in the economy. Just as these Internet generations have matured and stabilized, so has the World Wide Web and all of the very cool devices used to access it. All economies of the Western World are starting to be powered by professionals who have no affinity for print, and our industry must quickly accept this fact to stay relevant in the media mix. We can no more stop the momentum of on-screen communications than the dramatic drop in the value of used offset machinery, which is why most commercial printers are seeing that the industry has reached a watershed moment. This is not an easy business environment to accept, but lasting changes in the valuation of offset equipment are clearly underway. Game-changing moments Press manufacturers have seen this digital communications environment coming for years, in terms of overall market shrinkage and in the ongoing potential for offset. Granted most offset press makers were taken off guard with the degree of change underway, because of the huge financial fallout, but the situation has been hovering like a dark cloud for nearly two decades. Arguably, one of the most important moments in press evolution over the past half-century came in 1990 with Xerox’s introduction of its monochrome-based DocuTech engine. For years, printers viewed this machine as a fancy copier, but most offset press makers were immediately aware that they were facing a new competitor – digital printing – that would ultimately be better suited to the new world of communications. Xerox had been evolving its digitalprinting technology for decades, making a true breakthrough all the way back in 1959 with the 914 model, noted by the company as its first automatic plain paper copier. At the same time, of course, offset machinery was also evolving by leaps and bounds to reflect market needs, whether focused on adding more colour, quality, speed or automation. For example, although Heidelberg did not invent or even build the first 8-colour 4/4 perfector, the German giant is rightly credited with developing a workable, productive machine. This was also a game-changing moment in the traditional commercial-printing sector. Long perfectors, as these presses are sometimes called, have, in their own way, hastened the deterioration of assembly-line machine manufacturing. Throughout the late-1980s and early-90s (before the advent of online, at least in the sphere of the general public, and despite the meteoric rise of personal computing) competition in the business of communications was still only taking place amongst the various methods of printing, as press makers and printers alike tried to determine what would be the right technology for the future. The long perfector, for example, essentially wiped out the non-process colour market in favour of full colour, because work could suddenly be produced for the same price as monochrome jobs – often for even less price. Then with the arrival of computer-to-plate imaging, predominantly and proudly developed out of Creo’s Vancouver facility in the 1980s, print manufacturing became relatively quick and cheap by the 1990s, just as Xerox was starting to exert its DocuTech changes on the market, enhanced of course by the arrival of Benny Landa’s Indigo press design in 1995. Similar to the effect of long perfectors, the Indigo machine showed it would soon be possible to produce full-colour digital as cheaply as monochrome digital. With the official launch of Heidelberg’s powerful SM 102-8P during drupa 1995, I suspect that many of the company’s executives, while they understood this press would be game-changing, also felt its arrival marked the end of an era. That the arrival of this impressive new press was hitting a market peak, soon to be followed by an unheard of decline in offset press manufacturing going forward, although nobody from any of the big press makers could have predicted when such an environment would truly take hold. |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||