|

|

| Home › Articles › Here |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| By: Nick Howard | Date: June 2010 | Contact the Author |

|||||||||||||||

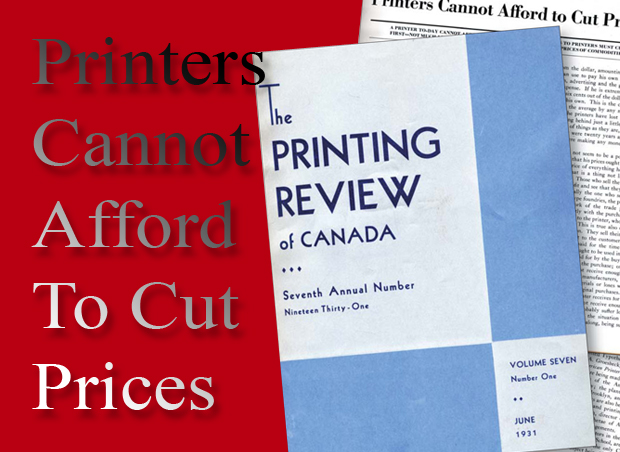

| Seventy-nine years ago, Canada’s flagship

printing magazine, The Printing Review,

included a feature article outlining why a

printer – in 1931 – would be making “the

mistake of their life” by reducing prices to

appease the buyer’s market. The article, entitled

Printers Cannot Afford to Cut Prices,

explains, that not so long ago, a printing

company could reduce pricing to secure a

job with the intention of making up the difference

on the next job – “but these other

ones are few and far between to-day, and

the wise printer knows it.” The June 1931 article continues: “The price for printing is something that cannot be successfully tampered with. If a buyer suggests that a printer must lower his price to secure an order, the following questions should be considered first: |

|||||||||||||||

Has the price of paper been lowered? Has the price of paper been lowered? Has the price of ink been lowered? Has the price of ink been lowered? Has the price of photo-engravings and

electrotypes been lowered? Has the price of photo-engravings and

electrotypes been lowered? Has the price of trade composition been

lowered? Has the price of trade composition been

lowered? Have wage scales been lowered? Have wage scales been lowered? Has the rent been lowered? Has the rent been lowered? Has the rate of depreciation been

lowered? Has the rate of depreciation been

lowered? Has the overhead been lowered? Has the overhead been lowered? Has the cost of power, telephone, etc.,

been lowered? Has the cost of power, telephone, etc.,

been lowered? |

|||||||||||||||

|

The Printing Review writer answers his

own list of questions with a vigorous

“NO!” – all-caps and exclamation mark

included – then emphasizes his point suggesting

that the only true reduction that a

printer can make is to their profit: “The

man who knows his costs and knows the

margin of profit he is operating on, soon

realizes that he cannot afford to cut his

price.” The writer then backs up the argument by referencing an article by Robert Maxton, from The Business Printer, who outlines the pricing pressures on your typical 1930s printer, emerging from a major worldwide economic meltdown. Maxton writes that about 40 percent of what the printer takes in for his product goes to pay for the purchase of paper, ink and trade work (bindery, composition, engraving, etc.), while another 30 percent goes to pay overhead costs like salaries, rent and taxes. “If he is extremely lucky, there will remain about six cents out of the dollar as a net profit, which he can call his own,” writes Maxton, about the 1930s printer. “In fact, nearly one-fifth of the printers have lost money in their plants and are slipping behind just a little bit each year. Not a pretty picture of things as they are, but they are vastly better than they were 20 years ago, when very few printing plants were making any money out of printing.” The search for margin, which, according to these articles, seems to have been printing’s Holy Grail for nearly a century now, will always be a major challenge for the industry. As such, printers in Canada need to adopt a new mantra solely focused on the ability to lower the cost of manufacturing print. You might, in fact, be surprised to learn how some (certainly not all) of your rock-bottom-price competitors are actually making money, and not just turning their press cylinders, for turning’s sake. Some companies have already changed their tune, from worrying only about price, and did so predominantly by investing in modern instruments of automation. Out of the old Nearly a decade before television was even known to the public, and some 50 years before the arrival of the World Wide Web, the printing industry at large felt hard done by the pricing pressures placed upon it by the marketplace. Reading through this old printing article, I found it fascinating how congruent today’s printing mindset is with the mindset of yesteryear. Certainly, today’s printing companies and their analogue product face even greater challenges, as new forms of on-screen communications seem to emerge from every possible form of device. When I listen to members of our industry today, many still recite the same 1930s mantra of downward pressures on pricing, seemingly unfair competition with wild and crazy prices that do not seem to make any sense. And while they are most certainly correct in citing such challenges, there is also some solace to be gained from understanding that the printing industry has always persevered under such pressures. |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||