"Those were the days, my friend, we thought

they’d never end . . . " The song popularized by

Mary Hopkin in 1968 waxed over youth, lost

opportunities, passions and a life now well past its prime.

Cycles of every form have a beginning as well as an end.

Technology breeds new revenues and fills scrapyards with

redundancy. For the printing machinery industry, there

is a lot of reminiscing about good times back in the day.

The great period of litho printing press sales, what almost

became an annuity business for press makers, is long over

and will not return. Oh how painful it is to say that.

It seems like only a few years ago we were so excited

to embrace a device that, either by violet or thermal laser,

entirely eliminated a labourious step of the production

cycle and make offset plates perfectly, without fit issues,

and at incredibly fast speeds as lasers advanced by the

month. Digital technology was our friend. Prior to CTP,

the Macintosh computer also eliminated a huge chunk of

the typesetting industry by letting us do it all ourselves.

Fantastic new devices were going to rid us of waxers, light

tables, film, cameras, plate-makers and a great deal of expensive

labour. Everybody knew that strippers and other

prepress employees commanded large paychecks. Wasn’t

this future fabulous?

As I look back at some of the projects we were involved

with at Howard Graphic Equipment, I find that no one really

had any idea of where mobile computing, particularly

the smartphone and tablet, would take communications.

We once had a customer who had a rather simple contract

to print a 10-point cover and then stitch it onto popular

magazines. It was for a now-defunct airline, to be used on

the aircraft. The airline wanted to ensure these magazines

were returned and so had produced the magazine with

its logo emblazoned on the false cover. In time, the costs

proved too high and the airline asked instead for a sticker

to be tipped onto the cover. Finally, the magazines as a cost

were dropped altogether.

Another customer produced a weekly sports betting

card. These were perfected one over one and printed in

the millions. Again costs and technology overtook print

and now all the betting is online, no day-changing betting

cards, just a receipt with the details.

In the early 1980s, we did quite a lot of business with

an accounting publisher. Every time there was a change

in Canada’s revenue act new sections had to be printed.

Even then hot metal Linotypes were used to make copy.

It was proofed and then film and plates were made to run

on a web. The bindery was enormous to handle the accounting

publisher’s work. It had separate lines for side

stitching, hole punching and perfect binding. The annual

tax-code book was almost two inches thick and expensive.

Accountants, who were members, bought special binders

for all of the inserts of changes that would occur each year.

The Internet almost overnight eliminated all of this mechanical

work and hundreds of jobs.

Many printers found themselves in the same situation

with legal books and court decisions. Changes in the law

created a great deal of print and case-bound work.

Think of the law offices up until recently, where huge

libraries stored the requisite purchases for dozens of sets of law books. If not annually mandatory,

dozens of new thick books spoke to a law

office’s prestige Automotive manuals and

parts books were a staple of a few of our

customers, too. In the turn of just a few years,

almost all are now out of print entirely.

In the early 1990s, my company Howard

Graphic Equipment purchased a Miller

perfector from a printing company in

the east of England. This firm had a long

history. They were ensconced in what had

been a carriage house, even had an 1800s

workable water closet. The biggest piece of

business for this printer was railway timetables.

Almost all of it is now redundant.

A smartphone can look-up the schedule

and buy a ticket to ride without any paper

being expended.

Wondering where all of the presses have

gone is an intriguing question. In a commendable

open manner, KBA in its latest

annual financial statements for 2013 approached

this difficult subject. KBA commented

that group sales had slumped 35

percent since 2006. Since KBA is heavily

involved in both sheetfed, web and special

presses (currency and metal decorating),

it has an almost split revenue business at

€571.9 million for sheetfed and €527.8 million

for web and special presses. KBA also

acknowledges that since 2006 its Web sales

have fallen 70 percent and sheetfed almost

50 percent. The statements also comment

that the Web business will continue seeing

retraction in the coming years. Should we

assume KBA, although heavily diversified,

is an example of what all major press makers

are going through? The answer is yes.

Competitors to KBA may argue that

the business of newspaper printing (long

a staple of KBA) exacerbates the drop in

sales. They may also suggest that perhaps

KBA had a smaller commercial and publication

customer base, or that what KBA

produced was not as suitable? But KBA

is a major supplier in both fields. On the

sheetfed side, KBA owns a major position

in packaging and Very Large Format

sheetfed printing. New in-roads in technology

have been poured into the Rapida

106 and 145 platforms. One surmises

with its packaging strength KBA’s only

real rivals are Heidelberg when it comes

to imaginative, multi-purpose machinery

for the carton industry. Komori and Manroland

also compete in this segment with

Manroland running a close third to KBA

and Heidelberg in press variants.

We as a machinery segment are a reflection

of you the printer just as you are

a reflection of your clients. Therefore. we

must assume printers cannot make the

math work when calculating return costs

for a large piece of machinery. Presses that

cost a million dollars plus are no longer

the prime piece of manufacturing gear

in a printing business. They may never

be again. There are exceptions of course.

Trade printers who do it cheaper, not better,

may consider new machines. Packaging

printers will because the business is

stable. Smaller commercial printers, however,

will not. They may buy used, but its

doubtful that a majority of shops can draw

enough profitable work to pay for today’s

engineered marvels.

Data was once the exclusive domain

of the printer and publisher. The only

way any kind of data could be distributed

was through a printing press. Google et al

changed all that.

|

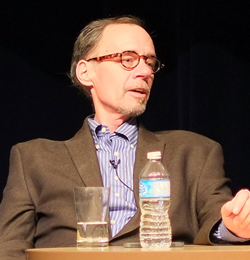

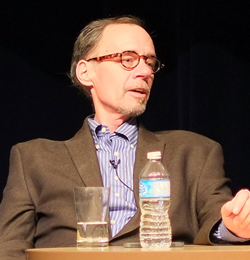

David Carr, writer for The New York

Times, does a masterful job explaining

how the trend from a physical method

(newspapers) to online is humbling.

During a recent speech in Vancouver, Carr

eluded to this fact when explaining the

state of his employing newspaper. It was as

much funny as it was sad for those of us in

the business. He explained newspapers are

offices where everyday information comes

in and is collected. Then a bell goes off and

everyone stops collecting news and starts

to write down what came in that day. They

send the copy to a giant press where it’s

printed, rolled up and eventually thrown

onto your front lawn.

Carr accepts the inadequacies of news

distribution via print while at the same

time considering that large dailies like The

New York Times seem to be weathering

the storm and seeing growth via online

pay-walls. Carr hastens to add that it’s the

medium-size papers suffering the worst,

while small local papers, for the most part,

continue to do well in the communities

they serve. News is data and so is almost

every piece of information we need, which

used to be mailed to us. First Gutenberg

and now the colloquial Google has

changed our world again.

|

David Carr speaks at the PuSh International Performing Arts Festival at Capilano University, in North Vancouver, BC.

Photo credit: "David Carr 2013" by Ian Linkletter

|

Despite the odd period of increased

new machinery order intake that prevailed

in late 2013, the industry at large will not

go shopping for new litho machines again.

While I have a vested interest, few press

makers would argue the second-hand

press business becomes more important

to lessen a printer’s investment risk. It is

not coincidence that used machines now

are a much bigger piece of the machinery

trading pie than ever before in the history

of printing or that most press makers now

have full-scale used press operations.

The 50 percent machinery sales shrinkage

in seven years, as reported by KBA, is

reality for every litho press maker. Postal

rates and other fixed costs are impediments

that cannot be overridden with

faster machinery costing millions of dollars.

Where have all the presses gone? Nowhere

it seems.

|