|

|

| Home › Articles › Here |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| By: Nick Howard | Date: October 2016 | Contact the Author |

|||||||||||||||||

As if a floodgate opened, 112

years ago the offset process

was born. Perhaps that’s

not completely correct.

Planographic printing

from a stone was an already mature industry

for metal decorating, maps and posters.

Metal decorating refers to an image

printed onto a sheet of steel. Variants of

this process also included the printing of

gelatinous transfer materials used as decals

for products that were not flat. Stone

printing was invented or discovered by

Alois Senefelder, a German, in 1796.

Crude as it was the possibilities of using

limestone as the “plate” excited a lot of

people. Doing the work, however, was

difficult and lithography remained a very

limited pastime until 1875.

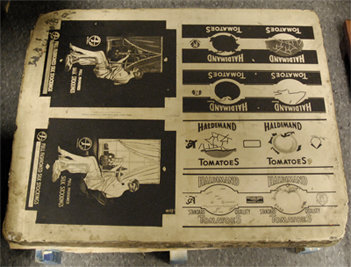

In 1904, Ira Rubel of Tenafly, New Jersey, ran a small print shop and discovered a missing sheet while his zinc press was on impression. Zinc printing process technology used a plate (zinc or possibly aluminum) with an image that was transferred directly onto paper. Rubel noticed the “wrong reading” image transferred to the subsequent sheet, was much sharper than directly from his plate – Eureka! Why had no one seen such an obvious thing before? It’s said that about the same year The Harris Brothers of Niles, Ohio, who had already revolutionized the letterpress world with a 15,000-per-hour machine called the E1, came upon the same discovery. Rubel then partnered with another man, Ike Sherwood, forming what was called the Sherbel Syndicate to make and sell his press. One went to Chicago and one to the J.C. Hall Co. in San Francisco just after the 1906 earthquake. Price of this press: $11,000. The others stayed in the east and the syndicate only allowed a few chosen printers the chance to own one. The idea of controlling a new technology proved to be a big mistake. This particularly riled Charles Goes of Chicago’s Goes Lithographing as he was locked out by the syndicate and he so desperately wanted in. Goes, which continues to this day, was a major producer of stock certificates and posters. All printed lithographically and with a stone. Goes knew the magic and possibilities of offset, how it worked and the fantastic advantages to his company. The Sherbel Syndicate was already falling apart two years later when Rubel left for England. There he contracted Bentley & Jackson Engineers to fabricate his design. But death soon followed in 1906 as did the demise of The Sherbel Syndicate. George Mann Engineers in Leeds got a hold of some of Rubel’s print samples that were left at De La Rue & Sons which spawned the British entry into offset in 1906. Restricted trade practices, hidden deals and lots of deceit were the unfortunate consequences of the earliest days of offset. The Premier-Potter Printing Press Co, later to be acquired by Harris in 1927, made all but one of Rubel’s machines and continued on their own after the collapse of Sherbel and death of Rubel. Kellogg was the other builder who like Potter started with Rubel’s crude press design.

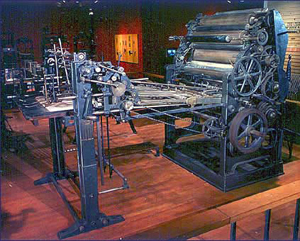

The real winner was the Harris Automatic Press Co. Charles Goes was so upset he caught the ear of Charles Harris. Now it should be said that Alfred Harris had come about the same epiphany much earlier. In fact, in 1898 at the offices of the Enterprise Printing Co. in Cleveland. While installing an E1 press Alfred is said to have heard foul language coming from a pressman and directed at a girl who had missed feeding a sheet. Wondering what the commotion was about Alfred came upon the same deduction as Rubel did years later. But Harris never acted upon it. Charlie Goes provided the fuel. He knew exactly what he wanted: a rotary press with three cylinders using a rubber blanket and a zinc plate. Harris struggled and tried to sell Goes a curved stone press, by Charlie said no, it wasn’t going to work. So Harris took a model S4 letterpress (22 x 30 inches) added a cylinder, modified it and came up with their first offset press! This press designated the S4-L was sold in 1906 to Republic Bank Note in Pittsburgh and now resides at the Smithsonian Museum. Goes received the next presses (possibly two) of the earliest design. A string of presses followed and placed Harris as the undisputed leader in offset. Printers from far and wide started reading about this amazing new technology that used a zinc plate, rubber blanket and impression cylinder. No type, no forms, faster speeds! Things got tougher, on two fronts. Firstly, the industry long known for conservative thinking, rebuffed offset as trash printing. Huge armies of letterpress suppliers ganged up on the fledgling offset makers to disprove the technology. Secondly, the early days of lithographic printing was horrible. Heavy zinc plates, big investments in ancillary machinery such as plate grainers, whirlers, cameras, chemicals, and expensive pressroom supplies were squeezing the most progressive offset printer. Even the Miehle Printing Press Company (the leader in letterpress machines) wanted no part of offset. It was not until 1922 that Miehle finally built one. Harris became not only a trailblazing offset pioneer but also provided substantial money to advertise what offset could do. |

|||||||||||||||||

Contact the Author |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||