|

|

| Home › Articles › Here |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| By: Nick Howard | Date: May 2017 | Contact the Author |

|||||||||||||||||

|

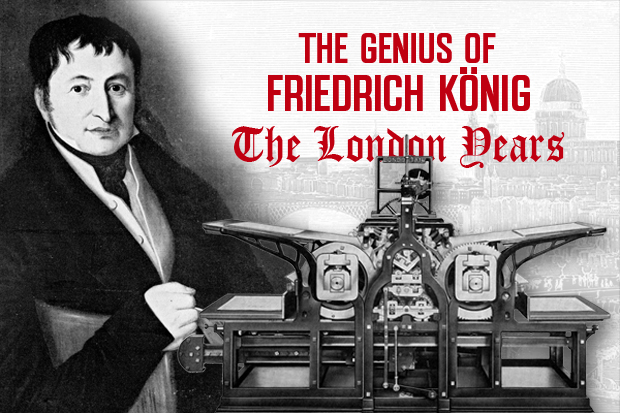

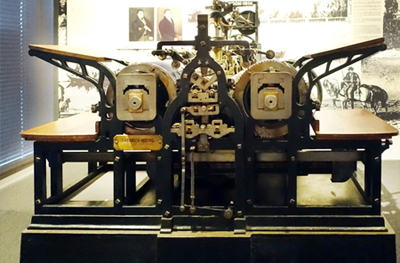

Friedrich König was a genius. If you visit either KBA’s Würzburg headquarters or the Gutenberg Museum in Mainz, you will see just how advanced his now famous The Times press is, built in 1814. With a 19th century fledgling printing industry labouring with only brute force, König created a massive advancement. I was stunned when I saw it: Such brilliance in a press, the first to not only have a cylinder but also endless tapes to feed a sheet. The most incredible feature was how König worked out a system with cams and gears to stop and start the cylinder and keep register to a moving bed. What may be even more stunning is how long it took afterwards for his concepts to become commonplace. All of it powered by steam. König’s creation would hasten the development of newspapers, making them cheaper and more readily available to spur the spreading of ideas. The year 2017 marks an incredible milestone for Germany’s König & Bauer AG, described today as the world’s second largest press manufacturer, as it will begin massive national celebrations later this year to mark its 200th year anniversary. I will begin the story of this crucial printing power by first sharing its London years. All roads to England James Watt’s invention of the steam engine in 1769 not only unleashed new thinking in the trade houses of Great Britain but stimulated thoughts and ideas from all sorts of manufacturing industries that relied on manpower, waterfalls or animals to drive machines. Watts’ invention caught fire all over Europe and spurred the Industrial Revolution, when steam lifted the burdens of manual labour. Friedrich König was born in 1774 in the Saxon town of Eisleben, which was most famous as the home of Martin Luther. After schooling, König entered an apprenticeship in a printing shop, then returned to University to study mathematics and mechanics. Afterward, he tried his luck running a bookstore and a printing shop. Both ventures failed. It was not until König relocated to Suhl (state of Thuringia) that he began experiments using steam power to operate a faster printing press. König had an incredible idea! Up until 1803, print shops were still using the rudimentary wooden presses almost identical to what Johannes Gutenberg created in 1450. By 1799, Lord Charles Stanhope had fashioned the first successful all iron hand press and the famous George Clymer Columbian was still years away. The printing industry was primitive with basic screw and wooden-handle presses. König wrote out a description of his automation ideas and sent prospectuses off to leading printers in Europe and Russia. With poor response, König decided to try his luck in the most advanced country on earth. England was ground zero for advanced engineering and also patents could be easily obtained. König managed to arrive only one day before Napoleon’s blockade of the channel and on November 20, 1806, he stepped foot on English soil.

It was Bensley’s job to hunt for prospects and newspaper publishers were a very good place to start. John Walter Jr. owned the venerable The Times newspaper and he had been utilizing new technologies. In 1804, Walter had entered into an agreement with a Thomas Martyn, who was a printer in Golden Lane (London), to finance the building of four new presses “by which manual labour in printing will be rendered nearly unnecessary”. There were stipulations on Martyn that these presses were for the exclusive use of The Times. After wasting £1,482 (£138,000 in today’s money), on Martyn’s Self Acting Press, Walter killed the project. On August 9, 1809, Bensley wrote to König: “Having occasion to leave town for the remainder of this week, I made a point of calling upon Mr. Walter yesterday, who I am sorry to say declines our proposition altogether.” The rejection by Walter forced Bensley to bring in additional financial partners and form a syndicate. The partnership now included Thomas Bensley, printer of Bolt Court, Fleet Street, Frederick König, printer of Castle Street, Finsbury Square, George Woodfall, printer, Sea Coal Lane, Ludgate Circus and Richard Taylor, printer, Shoe Lane, Fleet Street. None could offer anything more than money to the enterprise except König who himself had invested all his savings.

With the secret press set up at his workshop at Whitecross Street, König invited a Mr. Perry, the owner of the Morning Chronicle, and again Mr. Walter of The Times. Only Walter showed up and on witnessing König’s phenomenal machine in action he quickly realized what a leap it was and subsequently agreed to purchase two presses. Construction on The Times machines continued in secret at Whitecross Street. Andreas Bauer, now König’s manager and chief mechanic had each of his employees bound by a stamped confidentiality fidelity bond of £100 each. A sizable amount. By March 30, 1813, the syndicate and Walter had a signed contract. The agreement describes the goods as: “Printing by means of Machinery, two double machines of sufficient dimensions and capable of printing sheets 35 ½ inches in length by 22 inches in breadth, the letter press occupying to within one inch of the length and breadth thereof. Price £1,100 each with additionally two steam engines of two horse power - £250 each.” Walter was to have a 14 year exclusive agreement on the technology, save allowing the syndicate rights to sell machines for printing the Clarendon Bible and use by Government Printing Office. But if the machines not produce 1,100 sheets per hour (550 sheets per machine), then Walter had the right to terminate the contract and get his money back. As time went on, König was busy making parts for his presses and eventually delivered them to a special building owned by Walter near The Times at Printing House Square. All done in secret or so it seemed at first until The Times compositors caught wind of what was happening and demonstrated. The compositors feared that some would lose their jobs as the composing of duplicate pages would not be necessary. The rebellion was quashed by Walter, who was on hand on the night of November 28, 1814, to oversee the very first issue printed on König’s marvellous press.

|

|||||||||||||||||

Contact the Author |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||