|

|

| Home › Articles › Here |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| By: Nick Howard | Date: June 2018 | Contact the Author | |||||||||||||||||

|

United States War Department, eager to develop homegrown weapons, listened enthusiastically to what French revolutionary soldier Major Louis de Tousard had to say. He had learned the gun-making craft in France and was a staunch supporter of Le Système Gribeauval. It was the French who first began developing a way of manufacturing guns in a uniform method. In 1765, General Jean-Baptiste de Gribeauval argued for small firearms to be made with interchangeable parts for a range of reasons. Guns damaged in the field could not be readily repaired. Each part had to be reworked with files to fit. Hard to do in the midst of a bloody battle. Early attempts by American contractors proved daunting. In 1798, Simeon North, a scythe maker from Connecticut, was handed a cash advance to manufacture five hundred pistols. Later that year, Eli Whitney also received a contract. These two entrepreneurs labored over crude machinery in a quest to make identical interchangeable firearms in mass production. By 1822, John Hall, a contractor at the Federal Armory at Harper’s Ferry, announced he had finally succeeded in making pistols with interchangeable parts. Whether or not this is true, America was captivated by the new process to be named “armory practice.” Interchangeable Parts

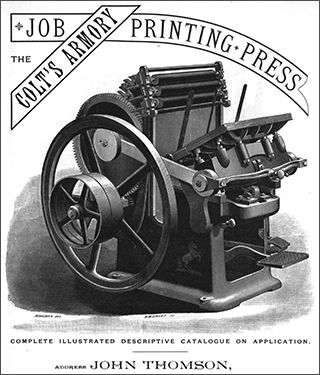

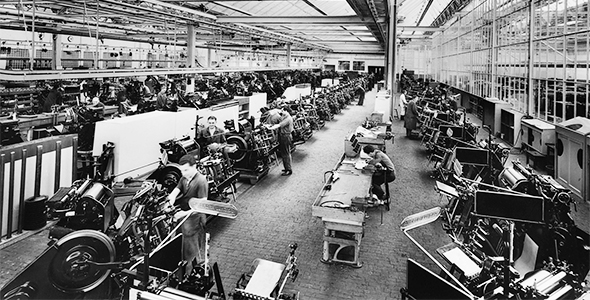

When the Singer Sewing Machine Co. needed a cheaper wood for its cabinets, it opened up a new plant in Cairo, Illinois, supply of gumwood was bountiful. However difficult to stain, gumwood was priced at $4 per thousand feet as compared to walnut at $50 per thousand. Singer made it work and in 1882 started churning out thousands of gumwood sewing machine cabinets with a great deal of internally developed woodworking machinery. More than 500,000 Singer sewing machines were being produced per year by 1880. Then the bicycle industry took off in the 1880s. Albert Pope had seen an English Smith & Starley two-wheel bike at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition. He started importing them as the Columbian Light Roadster and soon set up his own manufacturing factory. Although Pope used rudimentary armory practice, he was eclipsed by a Chicago firm, Western Wheel Works. Western found a cheaper way to make a bike using newly invented metal stamping for the wheels, sprockets, and chain. This practice eliminated all the machining that Pope and others back east were doing. Cheaper and faster was the result. “I never saw a job where the Western man would not beat the Eastern man out every time. You [Eastern men] know too much about tool making, and not enough about making money,” said Chicago mechanic David Hounshell in American Machinist (1895).  As jigs and gauges became standard, productivity would increase with the next big discovery. As formidable as it was in the late 19th century, Henry Ford would re-invent the armory practice in the early 20th century with his Model T assembly line and machine-shop practices. Ford re-thought factory layouts. Instead of placing, say, all the milling machines here and the lathes there, machine tools were laid out in a logical sequence to complete the process of making parts in a small space. Today, we’d call this Lean Manufacturing, but in 1913 Detroit it was revolutionary. Heidelberg Assembly Lines In 1926, just 13 years after Ford Motor Co., Heidelberg became the first in the printing industry to implement an assembly line. The American armory practice spread worldwide and everything from light bulbs to farm implements followed the rigors of exactness and more importantly the use of machinery to replace skilled and semi-skilled labor. Printing equipment in the plants of Roland, Miehle, Chandler & Price, and Linotype adopted the armory practice in some form.

“There can’t be much handwork or fitting if you are going to accomplish great things”, said Max Wollering, Ford Motor. Henry Ford produced 15-million model Ts. He made them all the same and affordable. But, America soon demanded more – more power, more options, more comfort, and at a cheaper price. This is the irony of free enterprise: One cannot stop improving and sit back and enjoy the fruits of one’s labor. We are all well aware of the power of new printing equipment today. One offset press can make two or more older models redundant. A factory floor doesn’t need a battery of presses anymore. One-tenth of the labor is required today as compared to just 20 years ago. Undoubtedly this showcases a renaissance for the printing industry, even if it’s now much smaller in size. Rigour in the calibration of color and software drives mechanical means and continually reduces the cost of print. To continue the journey, industry leader Heidelberg has correctly turned its attention to an area poorly served since mass production began. It realized how printing plants vary greatly in the use of devices and software. Push to Stop is Heidelberg’s solution. Bring discipline back in order to use the tools that already exist, reducing costs and increasing productivity. With run lengths dwindling, it’s more important than ever to drive out waste. Training, as with jigs and gauges, is a by-product of armory practice. The Web-to-Print giant Cimpress N.V., for example, likely doesn’t associate itself with armory practice, but in fact, it is the basis of its production. Various technologies from digital to offset, and lots of platforms, work seamlessly with an online ordering template to reduce costs and increase profits.

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Contact the Author | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||