|

|

| Home › Articles › Here |

|

|

|||||||

| By: Nick Howard | Date: November 2018 | Contact the Author | ||||||||

|

If you take a drive west from the city of Quebec and cross the St. Lawrence River, you come across an unusual site. Two bridges come into view. The Quebec Bridge (Pont de Quebec) is starkly dissonant from its neighbour only 200 metres to the east. Completed in 1919, it’s a massive steel truss structure with a tragic past. Today, it remains the largest cantilever bridge in the world. Originally conceived in 1903, the first attempt saw the bridge collapse during construction in 1907. Seventy-five workers lost their lives. A second attempt in 1916 met a similar fate when a large section, being hoisted into place, broke loose and fell into the river. That section remains at the bottom of the St. Lawrence to this day. Thirteen workers died during this incident. The bridge was finally completed in 1919, and although no longer used for cars, it is still in service for rail.

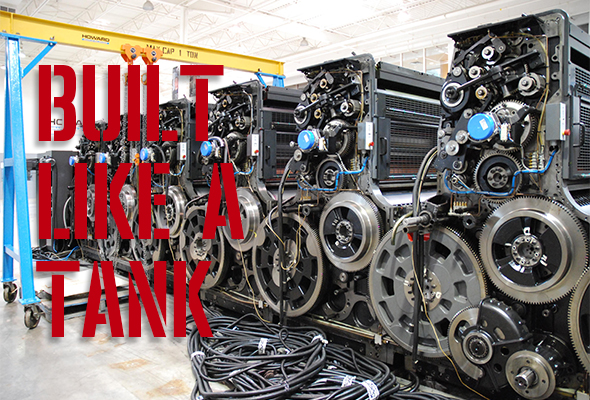

One can assume that getting a piece of paper precisely through an offset machine requires stability above all else. For over 100 years, the answer to this problem was to build platforms super heavy and with thick cast-iron side-frames and cylinders that look as if the press is going to be printing on quarter-inch steel plates. Over the century, presses have continued to be constructed this way with only the occasional nod to increased use of aluminum and magnesium castings to reduce the heft. Other than the infamous all-aluminum West Berlin Kiekebusch back in the 1950s, have press makers dared to deter from a common path of massive construction. That is until the advent of digital equipment. Just as others in the offset world, I too understood the advantages of massive construction. But over time and with much lighter digital presses elbowing their way into more and more pressrooms, I must say the industry needs to reconsider how they design and build legacy offset presses in an ever-shrinking landscape. With a typical transfer gear on a B1 40-inch press weighing at roughly 500 pounds, a typical single printing unit tops out at about 7.5 tonnes. A six-colour without coater 40-inch BI has a weight of roughly 59 tonnes. Compare this to a somewhat similar digital press, such as the HP Indigo 12000. The HP handles a maximum sheet of 29 x 20 inches and weighs just 11 tonnes all in. Although a smaller sheet size, the construction differences are startling. Perhaps a more relevant comparison would be the HP 20000 roll-fed version. With an image area closer to that of a 40-inch offset, the 20000 weighs in at only 15 tonnes. More weight translates into more costs in everything from raw materials, freight, rigging, power, and pressroom infrastructure. Digital equipment seems to have ignored the hallowed approach of the offset builders. Almost all digital has instead taken a different route, and this further exacerbates the line between the old and new approaches to print. With offset, you need three massive cylinders and a full ink and dampening train just to get a dot onto paper. Then repeat that for every colour. Digital requires just one cylinder for all six colours. In the mid-1980s, one press maker redesigned its ink train using hollow rubber rollers. The results were catastrophic, and it quickly returned to heaver solid core rollers. You can tell the offset guys are scared to death of tinkering with what is now a proven process. Embracing the very latest engineering technologies has encouraged younger minds to take a fresh look at how to build a printing press, which will most likely have a shorter lifespan compared to offset. They are feeding and transferring substrates using modern approaches without the bias of the older mature offset industry. Instead of bulky feeders that can hold 5,000+ sheets, they have simplistic feeding devices akin to long forgotten duplicating era. Plenty of punched steel side-frames, delrin gears and plastic! However, there are exceptions. Konica Minolta teamed up with Komori to slap its inkjet technology onto a staid, traditional Komori offset platform. Landa has done the same, choosing Komori for its feed and transfer elements. Heidelberg teamed up with Fujifilm recently, installing the first 41-inch Primefire 106 Speedmaster in the U.S. and Koenig & Bauer’s VariJet 106 is a joint venture with Xerox. All four designs are complementary in that the proven technology of a modern offset press coupled with inkjet can offer an assured outcome of sorts. But this may be temporary. Advances with pretty much all digital suppliers are happening at almost lightning speed, and the new digital kids may simply disregard the old timers and go it alone. For the likes of Konica Minolta, Canon and Fujifilm et al are fully aware it is they who now make the rules. Lighter weights also open the door to easier installations. Long vanished from most downtown city cores, offset presses are now generally found in outer industrial areas where they can get more power and in ground-level buildings. Digital presses can be installed virtually anywhere and with much smaller footprints. Arguments for such hybrid offset/digital presses are understandable. Speed is the most obvious. Light-duty machinery currently will not stand up to the punishment of daily use at offset-like press speeds so why not eliminate that factor? This is true, and traditionalists will defend that position out of common sense. “We make and sell printing presses — we don’t rent them!” But something will have to be done to get around the high costs of manufacturing offset machinery. Until then and with metal prices skyrocketing – especially aluminum alloys – press makers will keep collaborating with digital up-and-comers as they have no choice. One approach that is rather unique is the Heidelberg Subscription program of charging per sheet. Over 20 years ago, a colleague – who ran sales for a major press maker – pushed his company to create a program that basically rented a press to a printer for a fixed period of time. The concept was quickly shoved into a trash bin, and the comments were, “We make and sell printing presses — we don’t rent them!” It wasn’t the right time. Heidelberg’s reasoning is spot on. In an era of shorter runs, why spent three to four million on a 40-inch press when you can only pay for what you print? Backing all this up Heidelberg owns or controls a host of consumables under the brand Saphira and rolled that into the program too. The printer has no upfront financing and no costs of ownership. The company gets to concentrate on finding more work for the press, not finding finance partners. The digital industry, led by Xerox, invented the “click” charge and finally, a legacy press maker has embraced it. I think this is an excellent idea whose time has come in an industry that is constantly changing. The average printer is already used to clicks versus costs with its digital machines, and most don’t have the lemming-like desire to own technology that has a shorter and shorter technology lifecycle. When and until someone figures out how to raise the production speeds of digital platforms, the reliable over-built offset press will remain the stop-gap. Run lengths continue to fall and will accelerate the offset demise. As throughput increases, the two technologies will differ as much as the two bridges crossing the St. Lawrence. |

||||||||

| Contact the Author | ||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||