|

|

| Home › Articles › Here |

|

|

|||||||

| By: Nick Howard | Date: December 2018 | Contact the Author | ||||||||

|

Malcolm Gladwell’s 2008 bestseller Outliers garnered worldwide attention, posing the argument that successful people needed more than brains, ambition, hustle and hard work to reach the top. Gladwell reasoned they also required luck. Using various examples such as Bill Gates’ access to a university computer or the Beatles 10,000+ hours of practice, Gladwell postulated that luck combined with serendipity played a key role in one’s success. All those interminable nightclub dates in Liverpool and Hamburg polished Lennon and McCartney’s music. The same can also be said of Apple Inc.’s Steve Jobs. Xerox Corporation has a developmental lab in Palo Alto, Calif. Started in 1970, its purpose is to incumbent new technologies within the realm of graphic communications and to develop new tools for the exploitation of the Xerox business. Known as PARC, ground-breaking technologies such as the graphical user interface and the mouse came out of the research and development lab. Today, Xerox is the recipient of about half of the technology generated. Giants such as Fujitsu, Dai Nippon Printing Co., Ltd., and Samsung are also current clients of PARC. An invention without a market? The graphical user interface (GUI) is something we take for granted today. GUI is used everywhere. Anyone who stills remembers DOS and its brain-freezing use of the ‘F’ buttons will certainly be appreciative of this watershed technology, perhaps no one more than Steve Jobs. An urban legend suggests that Jobs gained access to PARC and upon seeing the GUI and the mouse, used it to develop the Lisa computer. Perhaps that’s not all accurate, but regardless, PARC indeed did invent the GUI and seemingly lost interest as the tie-in with Xerox toner-base printers was not evident or obvious. Jobs had been to PARC, and that is one fact that is corroborated. Another fact is some members of the Apple development team had also worked previously at PARC. Xerox PARC is also credited with inventing the personal computer. Our office bought one (a Star) around 1981. I recall it was really expensive; $16,000 comes to mind. That’s equivalent to $45,000 today! The PC was huge with a pack-to-pack dot matrix printer and monstrous 8-inch floppy discs. With minimal computing power in an era where simple word processing was prevalent, the Xerox PC quickly disappeared with the onslaught of both the Macintosh and IBM. Xerox’s Rochester neighbour Kodak owned the technology for the world’s first digital camera in 1975 when Kodak engineer Steven Sasson invented it. Kodak shelved this breakthrough for similar reasons as Xerox’s GUI. Both either feared the death of their bread-and-butter businesses or simply could not fathom a need, not realizing that they would get it all so terribly wrong. How do we sell more photocopiers if offices printed less? How would the fabulous film business cope when no one needed to buy film?

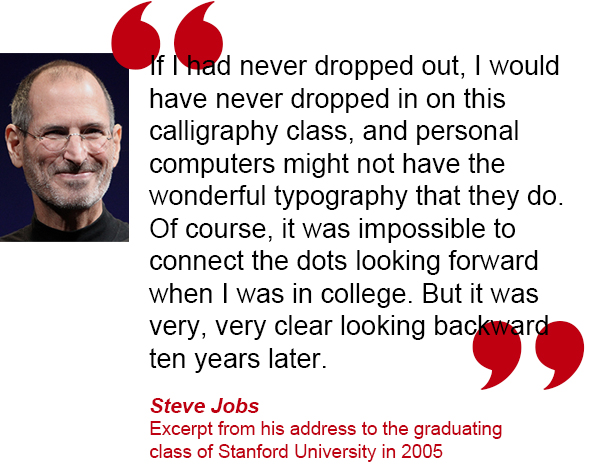

But within the space of the last 24 months, machines have gotten better and faster. So much faster that our industry is spoiled for choice on what to buy. Recently, Heidelberg unveiled two installations of its new Primefire 106 collaboration with Fujifilm; ColorDruck in Germany and Warneke Paper Box in the U.S. Not to be outdone, Landa Digital placed four of its S-10 40-inch presses in print shops of Germany, Switzerland and the United States. Océ’s ImageStream roll-fed, as well as the Konica Minolta-Komori joint venture (KM-1 and Komori IS29) and Fujifilm’s latest J Press 750S, are after years – if not decades – starting to find homes that were the exclusive enclave of offset. Inkjet in all its various manifestations has, in a relatively few short years, become an anchor of the printing process. Consider also the rapid developments with dry and liquid toner equipment from Kodak, HP, Xerox, Ricoh, and Konica Minolta. Toner has a fair share of the offset market as well. After drupa 2016, I heard negative opinions from some printers about the various demos they saw. Many complained that images were weak and rub-off was poor. Some brought up other key weaknesses such as available colour gamut or difficulties in post-press. Few seemed to be preoccupied with slow speeds or over-the-top price tags. Since 2016 things have changed and improved considerably and more to the point, printers seem to finally have connected the dots in how implementing digital as a replacement for offset makes profitable sense. Run lengths are still shrinking and quality is increasing – the perfect situation for slower platforms. Add in variable data and more SKUs and all of a sudden digital looks like a godsend. With a few exceptions – Landa, Heidelberg and Koenig & Bauer (who use legacy offset platforms) – are the only ones to offer a tower coater. Few, if any others have offered in-line coaters. This will no doubt be a welcomed addition in the near future. Fujifilm’s J Press 750S, released in November 2018, has already increased its output 33 percent compared to its first 720S model albeit still without a coater. We now talk months, not years, for rapid improvements in both speeds and flexibility. As we approach 2019, it would seem that Gladwell’s Outliers has finally taken a stranglehold on our print industry. Perhaps up until now the majority of printers collectively refused to think outside the box for the next great thing. In the next ten short years when our history is again rewritten, will we ponder why we hung on to [offset] technology that was over 100 years old? Or will we celebrate just how easy it is to produce beautiful work in all guises with the help of a mouse, a screen and imaging devices the size of a fist? Or even perhaps surprisingly, the invention of the PC and GUI, discarded as irrelevant, would be embraced by folks that could dream differently? I think Steve Jobs said it best when he addressed the graduating class of Stanford University in 2005: “I decided to take a calligraphy class to learn how to do this. I learned about serif and sans serif typefaces, about varying the amount of space between different letter combinations, about what makes great typography great. It was beautiful, historical, artistically subtle in a way that science can’t capture, and I found it fascinating.  “None of this had even a hope of any practical application in my life. But ten years later, when we were designing the first Macintosh computer, it all came back to me. And we designed it all into the Mac. It was the first computer with beautiful typography. If I had never dropped in on that single course in college, the Mac would have never had multiple typefaces or proportionally spaced fonts. And since Windows just copied the Mac, it’s likely that no personal computer would have them. If I had never dropped out, I would have never dropped in on this calligraphy class, and personal computers might not have the wonderful typography that they do. Of course, it was impossible to connect the dots looking forward when I was in college. But it was very, very clear looking backward ten years later. Again, you can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backward.” “None of this had even a hope of any practical application in my life. But ten years later, when we were designing the first Macintosh computer, it all came back to me. And we designed it all into the Mac. It was the first computer with beautiful typography. If I had never dropped in on that single course in college, the Mac would have never had multiple typefaces or proportionally spaced fonts. And since Windows just copied the Mac, it’s likely that no personal computer would have them. If I had never dropped out, I would have never dropped in on this calligraphy class, and personal computers might not have the wonderful typography that they do. Of course, it was impossible to connect the dots looking forward when I was in college. But it was very, very clear looking backward ten years later. Again, you can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backward.” |

||||||||

| Contact the Author | ||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||