|

|

| Home › Articles › Here |

|

|

|||||||

| By: Nick Howard | Date: May 2020 | Contact the Author | ||||||||

|

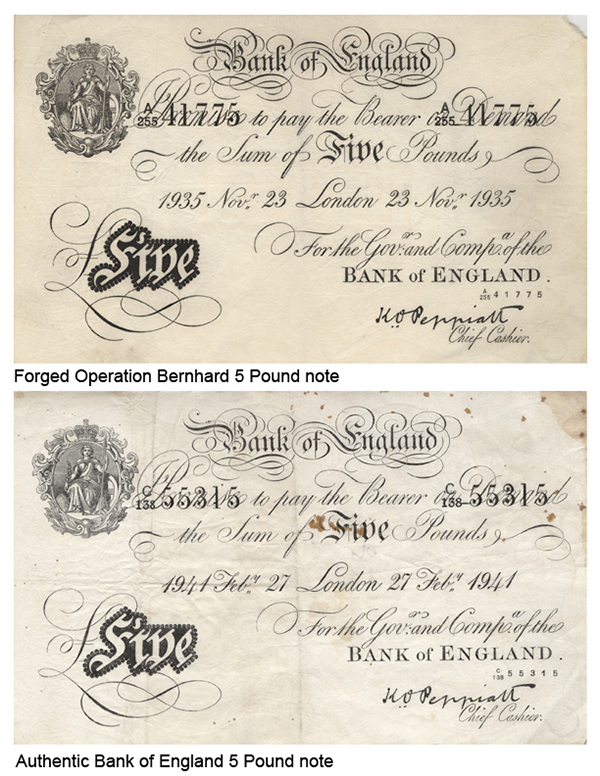

The Nazis counterfeited the most circulated British £5 note to use the fake money to finance German intelligence operations. S.S. officer Arthur Nebe had a devious plan. As the head of the Reichskriminalpolizeiamt (central criminal investigation department) in Berlin, the ruthless killer came up with an idea of forging British currency and dropping banknotes all over Britain, courtesy the Luftwaffe. The Second World War had just broken out as he presented his plan to the notorious Reinhard Heydrich, among others. Heydrich, considered a principal architect of the Holocaust, and whose nickname would soon be "The Butcher of Prague," quickly gave his approval, very hastily seconded by Adolf Hitler. The top-secret assignment would become known as Unternehmen Andreas (Operation Andreas). Dumping millions of English banknotes all over England would have caused widespread panic and chaos. The "Englanders" would never be able to utter the expression: "Sound as a Pound." Institutions could crumble, commerce frozen, and who knows what other calamities would follow? By early 1940, an equally loathsome character, Alfred Helmut Naujocks, set to work. First, with the difficult task of creating identical paper, then the printing plates. The paper proved to be a challenge. The British banknote was a special all-rag content paper, but in Germany, lignin was primarily available. Turning to the paper mill Hahnemühle in Dassel's northern city, various tests were performed without the cellulose addition. Still, the results proved unacceptable: the paper was simply too white! Someone suggested sending the rags to local industrial companies to use as cleaning cloths, then returning them to the mill to be washed and processed. An almost perfect match resulted, but this exposed a new flaw: The paper did not have the same crispness as the original. Trial and error eventually found the problem: the English water. After further experiments, this, too, was overcome, and the process continued with the next rather tricky task of replicating the incredibly intricate watermark. Beautiful screens using the cylinder mould-process were fabricated to produce a sheet of four notes. Banknotes were made – probably at, or near, Berlin – until Heydrich ordered an abrupt and unexpected stop. It seemed in 1940, Naujocks had fallen out of favour with a guy you didn't want to upset. The plan limped along with Albert Langer, a mathematician, and code breaker, who had been recruited for his expertise and abilities to decipher the alpha-numeric British serial numbers. Supposedly, some £500,000 worth of superb counterfeit £5 notes were printed by the time Heydrich pulled the plug by early 1942. None of the notes seem to have ever circulated. "The best way to destroy the capitalist system is to debauch the currency" – Vladimir Lenin. As early as November 1939, the British caught wind of the plot through a chance meeting in Greece between the British Ambassador and a Russian émigré, who spilled the beans. London was informed, and this brought about restrictions on paper money arriving in England from abroad. The Bank of England took a further step introducing a special "blue" £1 note with a security thread while also ceasing production of fivers for the duration of the war. All would not disappear, and the Nazis revived the plan in July 1942, with the encouragement of Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler. But the new program had a different mission. This time, the Nazis would counterfeit the most circulated £5 note and use the fake money to finance German intelligence operations, which were underfunded continuously by the Reichsbank. Himmler also had other wild ideas, including the forging of British stamps (laughably replacing King George's image with that of Lenin). A new man arrived to run the operation: SS Major Bernhard Krüger. Operation Bernhard would take its name from Krüger. Scouring the now-defunct Operation Andreas offices, Krüger located most of the copper printing plates, watermark screens, and printing presses; but needed printers. Skilled men were readily available at death camps, including Auschwitz-Birkenau. No persuasion was required when the selected Jewish prisoners' options were either a bullet to the back of the head or working in a print shop. The selection process focused on skills required, such as artists, typographers, machine operators, and cameramen. Historical documents suggest some Jews didn't have any of these skills, but to stay alive, insisted they were seasoned tradesmen. One hundred and forty-three men were selected and quickly transferred to the Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg concentration camp in northern Germany. Ensconced within the walls was a prison within a death camp where these men were isolated by barbed wire from the general population in two purpose-built barrack blocks, 18 and 19, and guarded by a select elite S.S. unit. Although history suggests Krüger wasn't a cruel man, every forger knew the German's allegiance to the Reich. And should any of them become unable to work or get sick, they knew the Nazis would simply shoot them rather than risk a trip to the hospital where the possibility of leaking the plan could expose the operation. Later in 1944, Krüger transferred a convicted forger by the name of Salomon Smolianoff to the unit. Smolianoff was a master, and although Jewish, he became ostracized from the other forgers who looked upon him as a "real forger" and, therefore, a crook. Smolianoff was an expert at forging, and the Nazis considered expanding their printing skills to include the American $100 bill. The Yankee Greenback proved extremely difficult compared to the £5 note because it was printed Intaglio and on both sides of the sheet. The British note was one-sided and without Intaglio.

Fortunes were made by Nazi collaborators laundering the money To launder the money, this fell upon a Nazi with a long history of deception: Friedrich Schwend. Schwend ordered that the finished banknotes should be delivered to a castle in the Italian Alps. Schloss Labers was an S.S.-run facility in the north Italian region of South Tyrol. From this castle, he distributed the forgeries to a variety of enterprises and individuals throughout Europe. Even Jews, as they would be seen unlikely to be collaborating with the Nazis. Some historians also believe £100,000 forgeries were used to earn the release of Benito Mussolini from Italian partisans in 1943. The funny-money spread as far as Turkey and Tangier. It was in Tangier, where the British finally caught wind of the forgeries. A banknote was compared with records in London, and the serial number was discovered to be a duplicate of an original note already remitted to the bank. Schwend would ultimately pass millions of pounds, many through Switzerland, Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands, and Yugoslavia. In the process, he became a wealthy man. The plan of paying the Nazi's bills was working perfectly. But by January 1945, the writing was on the wall. The Allies had already entered Germany from the west and south; Russians were even closer in the east, and the Reich clock was ticking. The men who worked 14-hour days and nights slaving in the cramped concentration camp were ordered to cease production and be relocated to the Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp in Austria, along with all the printing equipment. Krüger received orders to re-start the printing operation, but shortly on arrival at Mauthausen, another command was received from Berlin to stop production again. A further directive soon followed that had the Jewish prisoners transported to a nearby Vergeltungswaffen V-2 rocket facility, which also used forced labour: Schlier-Redl-Zipf. The operation was to be resumed once more, this time deep in the tunnels at Redl-Zipf, where the V-2 rocket program was in full swing. But the doors of opportunity closed. Krüger gave the order to destroy the equipment and remaining banknotes. By May of 1945, Operation Bernhard came to an end, and also it seemed, for the Jewish forgers, as Berlin ordered them trucked to nearby Ebensee concentration camp for liquidation. The forgers were divided into three groups, and on arrival, as usual, they would be sequestered from other prisoners until all three groups were together. There would be no chance for loose lips to give away the operation, and it would make the killings so much easier. Luck intervened as there was only one truck available and necessitated three separate trips. Two groups completed the journey, but on the third and final run, the truck broke down, and the prisoners were force-marched to Ebensee: a journey that took two days. Serendipity finally provided a blessing for the printers as the delay coincided with the fleeing of the S.S. soldiers at the camp and release of the first two groups into the general population when the populace overpowered the remaining soldiers. As the third group arrived on May 5, they too vanished into the crowds and finally released the very next day (May 6) when the Americans arrived. If the truck had not broken down, every one of these men would have perished! "No, I expect you to die, Mr. Bond!" – Goldfinger So what happened to all the fake cash? As was later discovered in 1959, the Germans had loaded up horse-drawn carriages and transported boxes of money, plates, and the printing machinery to Toplitz Lake nearby and dumped everything into a bottomless abyss. Unbeknownst to the Germans, everything would be preserved due to a lack of oxygen below 65 feet. Talk of a German forger conspiracy grew in intensity and worried both the British and Americans, as both feared an Alpenfestung (National Redoubt) or potential uprising in the Alps of Austria. The place was festered with what remained of the Nazi menace, and having a constant supply of money could reignite hostilities. In 1959, German magazine Stern, alarmed by a series of mysterious deaths near the lake, commissioned a dive to search for Nazi loot rumoured for years to be gold bars. Urban legend suggested a massive hoard of gold bricks lay at the lake's bottom, but none would be found. Amusingly in the 1964 movie Goldfinger, James Bond shows off a Nazi bar said to have been unearthed at Toplitz. The divers did, however, uncover a massive trove of wood crates with perfectly preserved £5, £10, £20, and £50 notes along with some U.S. $100 bills and printing plates. There was finally proof, but the British were already well acquainted with the affair. Right after the war ended, four men traveling from the Netherlands were stopped on entering England, and counterfeit notes were seized. One official remarked how rather unusual it was that four men would have bills with consecutive numbering on them. The Jewish prisoners were scattered on liberation, some never speaking again. Two men, in particular, have shed some light on events. Adolf Burger, who passed away at 99 years of age in 2016, was a Czech typographer who had been arrested early in the war for forging baptismal certificates for escaping Jews. Burger would later write a book of the horrors that also took his wife's life in Auschwitz. Avraham Sonnenfeld was from Transylvania, and his family owned a printing business. Although not highly skilled, Sonnenfeld was able to pass the Nazi rudimentary printing test (printing a greeting card). Most experts agree that Operation Bernhard forgeries were the finest ever seen. In 1967, a couple of pipe organ repairmen were dismembering an old organ in the Italian church of San Valentino. They were looking for a nameplate to determine the organ's age but instead stumbled across £5-million worth of almost flawless banknotes. The rippling effects of the Bernhard operation simmered long after the war, with notes popping up all over the place. The Bank of England did not even resume printing a £50 denomination until 1981 – such was the seriousness of the counterfeiting effort. Some allege that fake notes were also used by Jews to finance travel to Palestine in 1948.

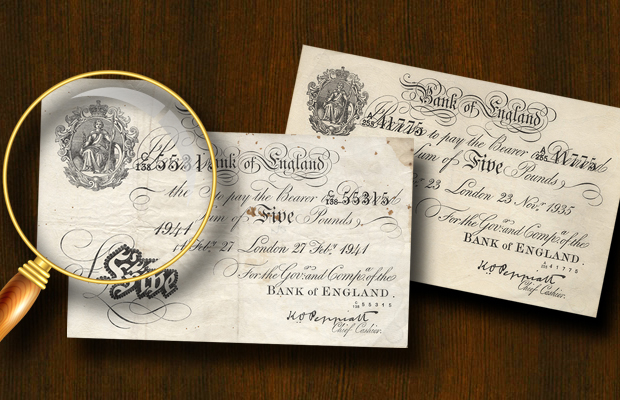

At Howard Iron Works Museum, we have one of the Operation Bernhard £5 banknotes and an authentic £5 note. The resemblance is remarkable in almost every detail, including the distinctive watermark – a virtual copy. No wonder experts pronounce these forgeries the best they've ever seen. The Hahnemühle paper company is still in business to this day but only producing innocuous artist's paper. Bernhard Krüger would go to work for them for a short time after the war. No one knows for sure exactly how many banknotes were produced during Operation Bernhard, or worse, how many escaped detection. One source suggests the value today could have been in the billions of Pounds. Let us not forget the 143 Jewish Printers who faced unimaginable horrors and completed such a monumental feat. They are the true heroes of this story and must be remembered along with the six million who perished at the hands of the Third Reich. |

||||||||

| Contact the Author | ||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||