|

|

| Home › Articles › Here |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

| By: Nick Howard | Date: Sep 2020 | Contact the Author | ||||||||||||||||||

|

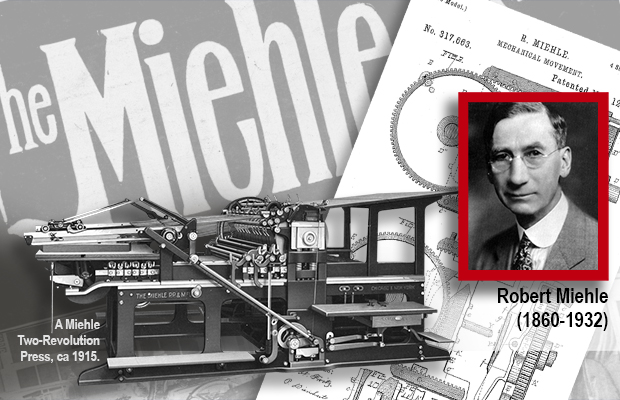

No one ever said business is

fair; it never was, and never

will be. The best and worst

of our humanity often surfaces under the guise of

“doing business.” It was during the wild

days of the 1880s in Chicago that a

23-year-old finished his apprenticeship

and graduated to the rank of pressman at

the famous Poole Brothers Printing Company. Frustrated with the constant clanging and banging of his two-revolution

cylinder press, Robert Miehle spent hours

on his back under his press, observing how

the “Mangle-Drive” functioned to move

the type-bed back and forth. The mechanical movement, first adopted by Germany’s Koenig & Bauer, was instrumental

in Koenig’s Times of London press of

1814. Although hi-tech engineering in

1814, the Mangle continued to be used

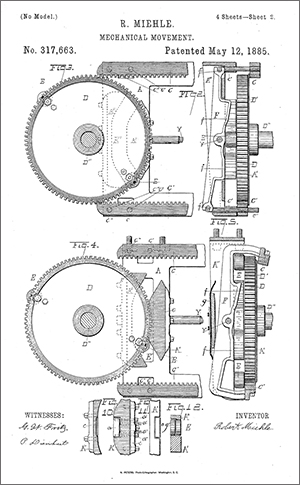

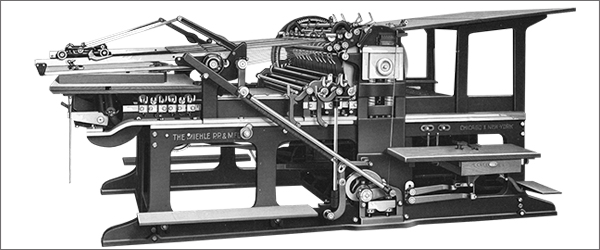

well into the late-1900s. Armed with a small notepad, Miehle began drawing sketches of potential design improvements. Without an engineering background, Miehle spent his off-hours studying books and learning the art of mechanical principles. He spent countless hours crawling under his press during the day, intently observing the drive and bed mechanisms. By 1884, Miehle had a solution; one that would drive the bed and cylinder in perfect harmony and, more importantly, eliminate the jarring that occurred with the Mangle! That same year, Miehle was issued his first patent, followed quickly by two other revisions. Most improvements don’t last for 60 years, but Miehle’s did What Miehle was able to accomplish would resonate for the next sixty years. Using a novel mechanical movement called “The Scotch Yoke”, Miehle then discovered Englishman Joseph Whitworth’s alteration known as “The Whitworth Quick Return Mechanism”, the imparting of a rotational force (gear) into a linear force (bed) with the bed increasing speed upon its return. Miehle’s design provided a much smoother, and ultimately superior, printing result. These mechanical principles were also finding their way into many other new technologies, including machine-tools and reciprocating engines. Large pipe organs were also early adaptors of the Scotch Yoke principle. Miehle claimed that, “a pica em quad standing on the bed would not be tumbled over even at a speed of 4,000-bed reversals an hour”. However, what was even more remarkable was that Miehle’s design displaced the cylinder gear, which removed the jarring effect of typical printing presses of the day.

By November 1885, Robert Miehle finally completed wood patterns and had the parts cast in iron at Tarrant Foundries. Once completed, the castings were taken to a Chicago Avenue printing shop where Miehle’s brother, John, was employed. After assembling the first press, word spread quickly through Printer’s Row saloons and a steady stream of industry types, from pressmen to owners, paraded through Miehle’s shop, all praising the design. Now all Miehle needed was something he never had: money. The old saying, “he doesn’t have a pot to pee in, nor a window to throw it out off,” summed up many inventors’ financial situations in the nineteenth century. Robert Miehle had to find someone to fund his new printing press.

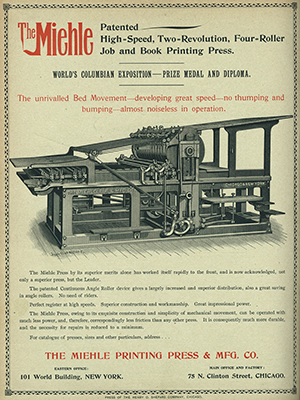

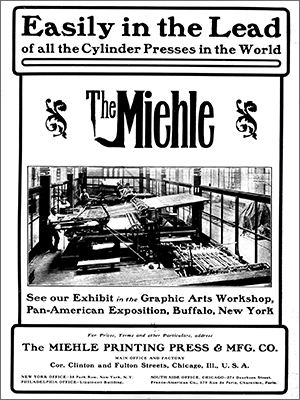

“Mr. Miehle, I have a proposition for you.” Samuel K. White would become that money source for Miehle. White already had a going concern at a building on Market Street, between Washington and Madison. Although known for his paging and numbering machines, White also dabbled in machine-tools and occasionally tried his lot as an inventor. White had even designed and constructed a paper cutter. It wasn’t long before White realized the significance of Miehle’s invention. In short order, White rustled up two business friends to form a partnership of what would become the iconic Miehle Printing Press & Manufacturing Company. On December 8, 1890, the three men convened for the first meeting of the new company. However, Robert Miehle wasn’t invited. Miehle had no way of coming up with his share of the $50,000 seed money ($1,415,000 today). Instead, Miehle cut a deal directly with White that would have his patent rights assigned to White in exchange for a royalty on all presses sold and a ten-year contract as chief designer. The company that bore Miehle’s name would ironically never have Robert Miehle as a shareholder; a blunder he would come to regret. The first press produced by the newly incorporated company would leave the White factory in March of 1891, and to the surprise of Robert Miehle, would not bear the name “MIEHLE” on its side-frame, but instead, the name “S.K. WHITE,” in bas-relief. Our Howard Iron Works Museum has one of these early S.K. White machines. Business became so brisk that the factory expanded later in the year and moved to the corner of Clinton and Fulton Streets in Chicago. With profits rolling in, the three partners were making substantial returns on their investments. Robert Miehle, stung by his gullible mistake, left the company in 1892 only to return later that year after his compensation was increased, and the “S.K. WHITE” moniker was replaced with “The MIEHLE P.P. & MFG CO.”

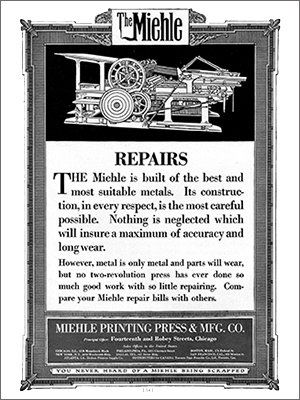

Quickly the Miehle Printing Press Company gained a substantial share of the world market, which positioned them at the pinnacle of a burgeoning sheetfed printing industry. A timely encounter with a Milwaukee inventor in 1920 would provide another milestone for the company. Edward Cheshire had designed a new little 13 x 19-inch printing press that ironically used the “Stop-Cylinder” principle long discarded by Miehle. Instead of a normal horizontal plane of the type bed, this machine held the bed and type vertically. The Miehle Company soon latched onto this concept as they were looking for a small “jobber” to complete their offerings. In 1921, Miehle purchased Cheshire’s “Milwaukee Automatic Press Company,” and the now renamed “MIEHLE-VERTICAL” would quickly become a top seller; remaining in production until 1974! After some research, I estimate well over twenty-two thousand MIEHLE-VERTICALs were manufactured. “You never hear of a Miehle press being scrapped.” Considering the length and breadth of the Two-Revolution Miehle success, including Europe, Scandinavia, South America, China, Japan and most of Southeast Asia, Miehle would reign as the undisputed leader in its field. The Chinese even printed currency on a Miehle, and the Swiss loved the Miehle, especially for printing Bibles. American and Canadian printers would also purchase the lion’s share of Miehle presses for generations to come. Robert Miehle would live until 1932, but his legacy and name would remain at the forefront of the North American printing industry until 1990, when Rockwell International (who had purchased MGD in 1969) discontinued what had been a 39-year relationship with Germany’s Faber & Schleicher, now known as Manroland. Since 1951, every Roland press that arrived in Canada and the USA was emblazoned with the MIEHLE name. It wasn’t until several years after Manroland’s arrival that the Roland name would supplant that of Miehle to Americans and Canadians alike. Ironically, I have one of those “six degrees of separation” tales concerning Miehle. The Toronto Type Foundry represented the Miehle Company for decades, going back to before 1912. My father worked for TTF, and I remember when he came home and told the family TTF was closing their doors. Miehle (which was now part of a triumvirate of three businesses – Miehle, Goss, and Dexter) decided that they (MGD) wouldn’t renew TTF’s contract and would instead sell directly in Canada. In 1966, TTF simply closed shop after being in business since 1887. The TTF owner was Mr. W.J. Palmer, whose family roots went back to San Francisco in 1878 and a type foundry and press builder known as Palmer & Rey. MGD’s destruction of an 80-year-old sales partner remained an invaluable business lesson I have never forgotten. When you work for, or represent a manufacturer, nothing is assured, and you might go to bed a peacock, but awaken as a feather duster. My father’s abrupt unemployed status resulted in our company, Howard Graphic Equipment Ltd. Perhaps had it not been for Robert Miehle, I may never have written this article. There was an old slogan Miehle often used: “You Never Hear of a Miehle Press Being Scrapped.” Robert Miehle was no doubt proud of that phrase and, more importantly, of how, as a young man of twenty-three, lying on his back in a noisy and hot Chicago pressroom, he discovered such a breakthrough that would change the face of print for almost 60 years! |

||||||||||||||||||

| Contact the Author | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||