|

|

| Home › Articles › Here |

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| By: Nick Howard | Date: Oct 2020 | Contact the Author | ||||||||||||||||

|

As a kid, I found attending

church dull, other than

one particular Thanksgiving

Sunday service observing

a mouse ravaging a

display of gourds, corn and pumpkins

while our Pastor bellowed away. Besides

sheer boredom, I often recall a great deal

of clergy finger-pointing with dire warnings

of eternal damnation. Hey! I was just

a kid, innocent to the world’s darker side;

let me grow up first. I never grasped why

preachers often showed antipathy towards

the congregation. Still, there were

two principles I credit to church-going:

don’t lie and don’t steal. Perhaps I was not

alone, as decades later, I learned of another

kid with a similar experience over a

century earlier. Fresh off the boat, a young Scottish lad named John Thomson soon found himself nailed to a pew at the Marion Presbyterian Church just east of Rochester, New York. The Thomson family, newly emigrated from Foonabers, Scotland, sought a new life and more significant opportunities. From 1866 to 1869, the teenaged Thomson, eyes glazed over, developed two vexations. First, the pastor harangued loudly. Second, he spoke with a strange (Yankee) accent. The Scotchman’s burr clashed with a Western New York twang. The Reverend was a fiery western New Yorker by the name of Merritt Gally. Young Thomson immediately disliked Gally, and this hatred would survive both men for the rest of their days. Gally had been an apprentice printer before he altered course to enter the clergy instead. At a young age, he learned engraving and design and worked for his stepfather, a master mechanic. The knowledge of mechanical engineering would come in handy. After a year, Gally designed and constructed his printing press while opening a print shop with his brother. But the pulpit beckoned, and Gally gave up his life of print in exchange for the Bible. A short three years later, Gally was forced to retire from the ministry due to severe bronchial health problems and threw himself back into the printing world. This time Gally used his obvious high intellect to invent a radically new printing press. What transpired was a platen superior to anything on the market, utilizing a never-before-seen mechanical movement. The Universal, as the press would be named, was born in 1869 in New York City.

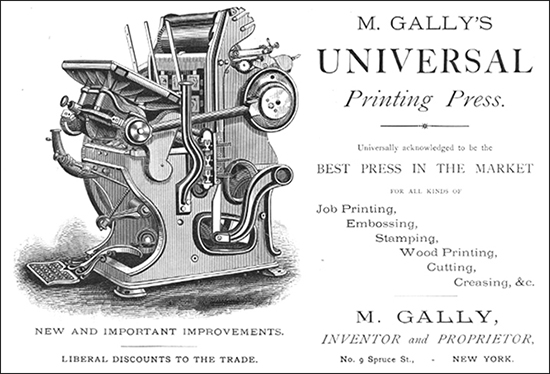

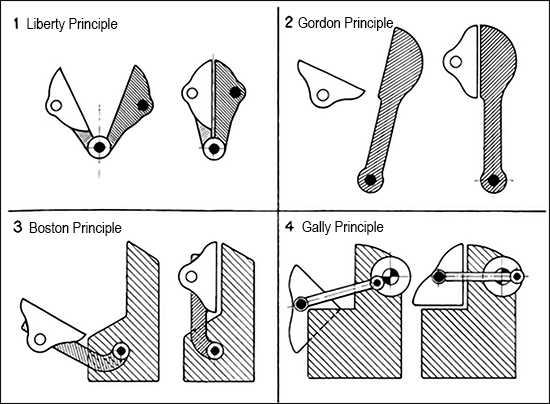

Before Gally’s press, there were three major types of construction: the Gordon, Boston and Clamshell (often referred to as Liberty). Gordon took its name after the American inventor George Gordon and appeared in the 1860s. Eventually manufactured in the hundreds of thousands by many builders, the Gordon Principle held the upper hand and the lion’s share of the exploding print industry. Gordons were produced not only in the United States and Canada, but also in Britain and Europe; if you have ever seen a Chandler & Price, you’ve seen a Gordon. The Boston principle would also receive wide recognition, mainly after Heidelberg chose it as the famous T Platen press’s foundation in 1914. Boston is a simple design of the platen pivoting on a spindle and “swinging” up to meet the bed. Finally, the Clamshell (or Liberty) worked just as the name implies, similar to a clam hinging open and closed, and as a result, proved to be the least expensive to manufacture, but the one with the weakest design. Often these types of machines were endowed with the most outlandish names, such as Dauntless, Lightning or Merveilleuse (marvelous in French). Marketing was important in attempting to attract buyers for these inferior imitations. The Gally “Universal” is now referred to as the PARALLEL IMPRESSION due to the platen’s unique action that, instead of swinging into the bed, was directed by a massive “S” shaped cam to become perfectly parallel just before making contact with the type matter. In a short period of time, the Gally would become the talk of the Northeast. In later years, the Gally would also be nicknamed the ART PLATEN for its superior impressional strength.

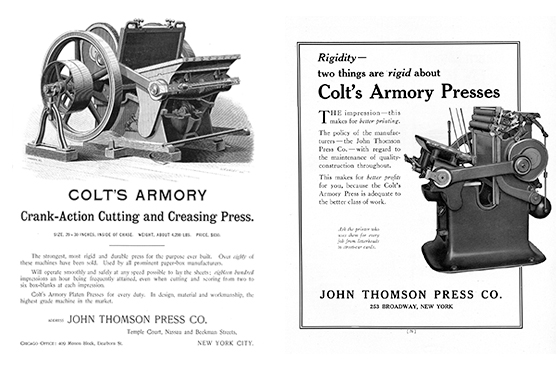

Gally was outraged. This former preacher breathed fire as he aggressively litigated against Colt over the theft of his design. But Colt and Thomson would win the case as the patent laws were clear, and Colt owned all the tooling, patterns and machinery to make the press. Gally attempted to continue, but his days of press building were winding down. The National Machine Company of Hartford would take over the original Gally design but would eventually be purchased by Thomson to form the firm that still exists today: The Thomson National Press Company (1923). However, there were other opportunities for Gally outside print. One of these was Gally’s improvement of automatic musical instruments and construction of the Orchestrone and Gally automatic piano. It was claimed that nearly all modern pneumatic church organs were equipped with his `back vent’ pneumatics.

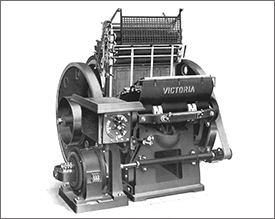

Thomson was most likely delighted to see his nemesis go down in flames in a New York courtroom. And between 1886 and 1902, John Thomson would remain employed at Colt. By May 1, 1902, Thomson succeeded in purchasing the complete press-manufacturing division from Colt and relocated the business to Long Island City, N.Y., where a new factory was completed in 1906. Several models were supplied, generally for printing. The Universal design’s robustness also established an unexpected opportunity in the rapidly- growing paper-box industry where the platen proved superior to all others. Universal’s superiority brought about rapid changes, now relegating the printing version to obsolescence. Larger, even more robust platens were designed, and Thomson quickly caught the attention of the Germans. Dozens of European (primarily German) firms started to copy the Universal, and most included inkers for printing. One of the most famous machine builders was the “Victoria,” manufactured in Leipzig. The Italians’ Nebiolo and Saroglia, even the famous German Planeta, offered a version. As time went on, the original Colt’s Armory presses faced stronger competition from German imports entering Britain and the U.S. Victoria offered multiple options and many enhancements not available on Thomson’s presses. By the end of World War I, Thomson had been building machines exclusively for cutting, creasing and embossing. Thomson even designed the first heated bed for heavy embossing and foil stamping. After the Second World War, the desire for larger cutting platens increased tremendously and attracted further newcomers. As always seemed the case, these new builders also hailed from Europe. The results were a much wider availability of super-large sizes explicitly built for cutting and creasing. Three iconic manufacturers, Rabolini (Imperia) from Italy, Crosland from the U.K., and Kerma from Germany, held top positions, especially for die-cutters larger than 40 inches (102cm). During the early 1970s, Eberhard Sutter (Spain) quickly picked up market share as the hand-fed business and high manufacturing cost placed the German and British at a significant disadvantage. Sutter (now owned by Spanish firm Cauhé) rapidly expanded their production, even offering a massive 71” x 126” (180 x 320cm) version.

As the 1980s wound down, the Chinese had awoken from a deep Mao-induced hibernation and had no trouble dealing with environmental issues that so plagued American and European foundry operations. Add in cheap labor, and virtually overnight, hundreds of versions of the Universal were being manufactured in the thousands. The competition was so intense that often the Chinese would produce copies of copies of copies. Quality control was especially problematic during the 1990s, but the selling prices were incredibly low, and sales to Europe and America did nothing but increase over time. During Thomson’s lifetime, there were no safety devices on these rather dangerous presses. The only protection was whatever was between the operator’s ears. Mechanical clutches soon eclipsed the old fast-and-loose pulley and was superseded by pneumatic and electro-magnetic clutch/brake combinations. It was a relatively normal instance to see men walking around a shop missing digits or complete arms: everyone knew the cause. Today these types of Universal platens are still counted in the thousands and in operation worldwide. They are used in the gasket and veneer industry and print’s own point-of-sale signage and display sector. Due to fast make-ready, the Universal platen today remains an ideal tool for very-large-format work. Only recently has new technology made inroads in displacing the Universal. The Swiss firm Zund and the Belgian Esko-Kongsberg are two of the most popular CAD cutting table manufacturers. While being slower, these machines don’t require a steel rule die and take advantage of software that allows the operator to do very little work. As run lengths decrease, these platforms have a negative impact on the Universal platen press. Just as the offset press’s twilight is close at hand, with digital presses making substantial progress, the programmable cutting table is knocking off a 151-year-old technology that is easily the printing industry’s longest and most successful production tool. After all these years (1869 to 2020), the Gally-Universal press continues to be called something that it isn’t; a Clamshell platen. The correct designation is a Parallel Impression platen. Merritt Gally’s brilliant invention and John Thomson’s improvements have stood the test of time. Just think, it all started in 1866 in Marion, New York, when a Scottish boy met a Yankee Pastor and they somehow developed a lifelong dislike of each other. |

||||||||||||||||

| Contact the Author | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||